Mahadol (Palanquin), c. 1700–1730

Gilded wood, glass, copper, and ferrous alloy

Gujarat

This splendid carved-wood and glass palanquin known as the Mahadol (grand palanquin) was brought to Jodhpur as war booty by Maharaja Abhai Singh (r. 1724–49) from Gujarat. A symbol of kingly prestige, the Mahadol was carried on the shoulders of 12 men and was used during festivals or marriage celebrations by the ruler and queens. This palanquin’s form is highly architectural, from the elegant curved roof (reminiscent of 17th-and 18th-century Mughal and Rajput architecture) to its arched doorways and windows. The base features delicate, lattice-like carvings of plants framed at joints by floral brackets that curve to form peacocks.

Krishna Jhula (Cradle for Krishna), late 19th century

Gilded wood, glass, paint, and lacquer

Rajasthan

The devotion of the Jodhpur maharajas to Lord Krishna was often expressed through lavish patronage of objects used in religious ceremonies. During the festival of Janamastami, which celebrates the birth of Krishna, the small idol is placed on the jhula for devotees. This splendid jhula is assembled from carved pieces of gilded wood with mirrors to enhance its magnificence. Peacocks, parrots, elephant heads, and mythical creatures like makaras and apsaras (fairies) decorate the jhula. The Rathore coat of arms is engraved on the bottom, signifying the use of the swing for personal worship by the Jodhpur royal family.

Huqqa (Water Pipe, Base) Bidriware, mid-17th century

Bidriware, zinc alloy, and silver

Bidar

Bidri, or bidriware, is a type of metal inlay work named after Bidar, a town near Hyderabad. It is instantly identifiable for its unique visual language of intricate designs in silver or brass revealed against a black zinc alloy. Jodhpur’s rulers would have been introduced to bidri and other Deccani arts while stationed in the region on Mughal military campaigns.

Floral decorations on these two huqqa bases are executed in two different techniques. The former carries highly restrained, typically Mughal floral motifs, while the patterns on the latter, the composite, lily-like plants, are more exuberant, with the windswept effect identified with a more indigenous Deccani idiom.

Baradari (Pavilion), 19th century

Wood, paint, lacquer, and gold

Jodhpur

A baradari is an open pavilion usually made of marble and sandstone. They were built amid Mughal gardens and summer palaces and were sites of leisure where men and women enjoyed music, drinking, and games. This portable garden pavilion from Jodhpur is assembled from wooden components which allow for easy transportation. Painted and covered in gold leaf, it is set up for a traditional board game called chaupar. The popularity of chaupar in Jodhpur is demonstrated by the game’s depiction in paintings and from the inclusion of chaupar sets made of expensive materials in royal dowries.

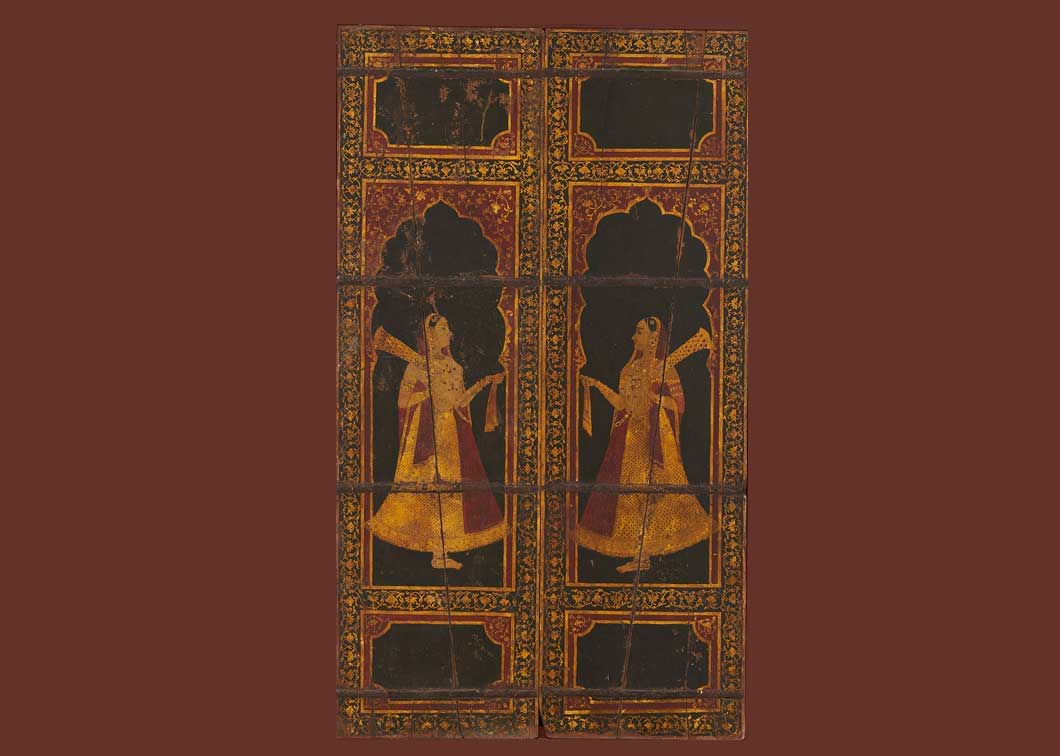

Painted Darwaza (Doors), 19th century

Wood, paint, lacquer, and gold

Jodhpur

This painted door, originally part of the palaces of Mehrangarh Fort, depicts female attendants. Two delicately painted figures on the primary side hold peacock-feather fans—a royal insignia—and silken rumal (handkerchiefs). Among three pairs of figures on the verso, the second pair of women hold out paan (betel leaf) boxes. The figures’ clothes and jewelry are indicative of courtly fashions in 18th-and 19th-century Jodhpur. Such attendants appear in paintings as well as in a rare late19th-century photograph of Maharaja Jaswant Singh II (r. 1873–95) and his concubine Nainijaan.

Mugdar (Clubs), 19th century

Wood, paint, lacquer, and ivory

Jodhpur

Wooden clubs or Mugdar have been used for centuries in Indian akharas (traditional gymnasiums) to build upper body strength. This highly ornate pair is considered to have been made for a female patron. They point to the importance placed on the physical training of royal women to prepare them for life as queens who were responsible for the safety of the fort and its inhabitants while their male relatives were away on military expeditions. Paintings from the 19th century suggest that royal women were trained to ride horses and wield weapons including guns. Paintings also depict women from the zenana accompanying the Maharaja on hunting expeditions.

Mir-e-farsh (Carpet Weights), early 19th century

Wood, camel bone, paint, and brass

Jodhpur

Carpet weights, known by the picturesque Persian term mir-e-farsh, or “lords of the carpet,” were used to hold down the corners of light summer carpets. The finials of this set are made to resemble lotus buds, a form frequently used in India on finials of all kinds. What makes these objects unique is their material—they are fashioned from pieces of painted camel bone attached to a wood base. Camels, raised by pastoral groups known as the Raika, were once integral to the economy of Marwar. They were used to transport people and goods across trade routes cutting through the desert.

Gangaur (Idol of goddess), mid-19th century

Silver, silk and gold jewelry

Jodhpur

Gangaur is a form of the Hindu Goddess Parvati, wife of God Shiva. Every year in Rajasthan in the weeks following the spring festival of Holi, silver idols such as this become the focus of an 18-day festival known as Gangaur. The festival is especially significant for Rajput women who observe fasts and offer special prayers during this time either for the longevity of their husbands or to beget good matches. In Jodhpur, festivities end with a grand puja led by royal women in a temple within the Mehrangarh zenana. The idol, dressed like a Rajput princess, is then taken out in a procession through the fort and the city, representing the goddess’s return to her marital home. The procession ends with a puja of the idols of the goddess and Shiva together and their symbolic immersion in water.

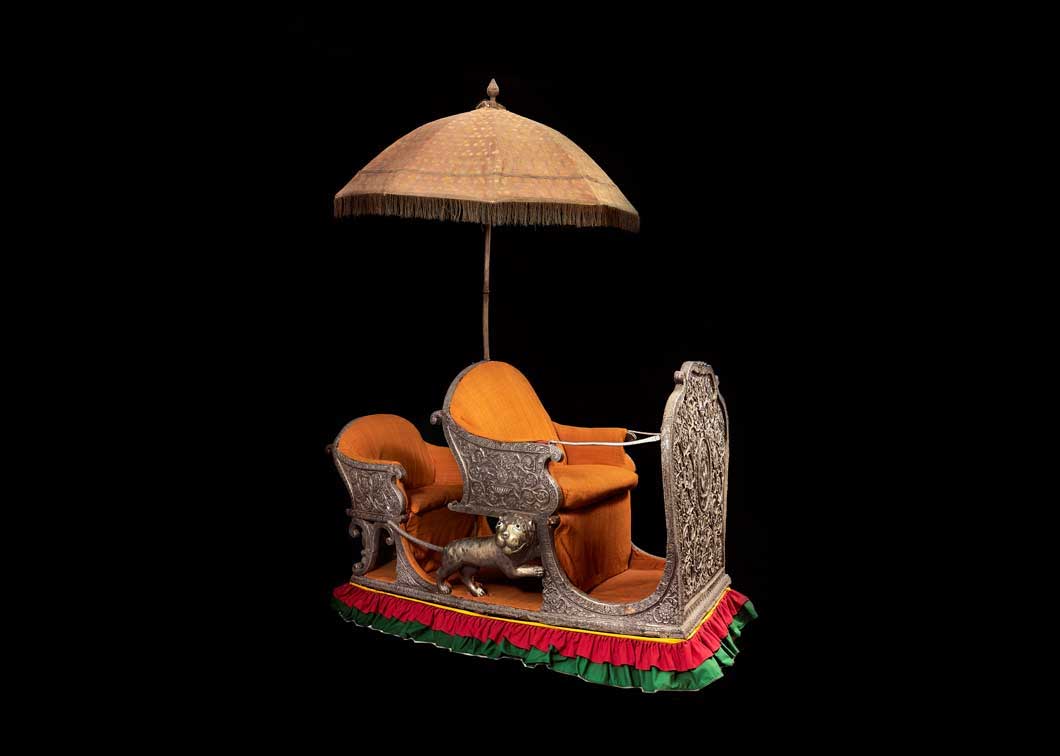

Howdah (Elephant seat), 20th century

Wood, silver, enamel, silk brocade

Jodhpur or North India,

Elephant seats known as howdahs were fastened on the back of an elephant for riding. During royal wedding processions, the groom rode a caparisoned elephant seated on howdahs. The procession is the most dramatic and public aspect of the celebration of an Indian wedding. In Marwar, royal wedding processions combined spectacle and splendor with the reinforcement of kingly prestige and authority.

This howdah of wood is covered in gold leaf and sheltered by a red silk-velvet canopy embroidered in silver gilt thread. It holds two seats: one for the Maharaja and the other for an attendant bearing yak-tail flywhisks (chauri).

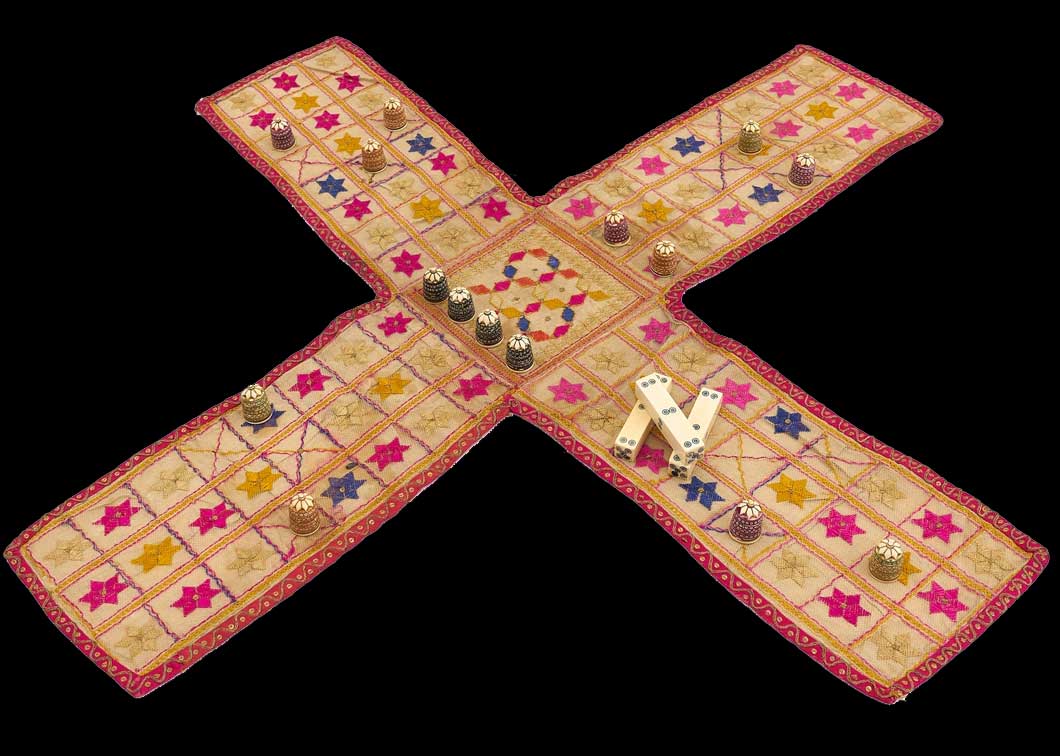

Chaupar (Game Set) with Goti (Pawns) and Pasa (Dice), late 19th century

Cotton, silk, silk thread, and silver-gilt thread, Painted ivory

Western India

A blend of chance and tactical skill, the game of chaupar was extremely popular in aristocratic circles. The four-sectioned board marked with playing squares is usually made of cloth. The players used 16 dome-shaped pieces called goti and three stick-shaped dice called pasa. Here, is a set of the game that includes the chaupar made of Cotton, silk, silk thread, and silver-gilt thread, set of painted ivory pawns (Goti) and a set of painted ivory dice (Pasa).